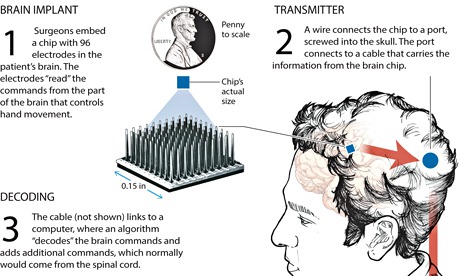

A port in Ian Burkhart’s head carries signals from a chip implanted in his brain to a computer. Photograph: Lee Powell/Washington Post

A port in Ian Burkhart’s head carries signals from a chip implanted in his brain to a computer. Photograph: Lee Powell/Washington Post Electrodes on Ian Burkhart’s arm designed to respond to signals from his brain, stimulate muscle fibres and cause movement in his paralysed hand. Photograph: Lee Powell/Washington Post

Electrodes on Ian Burkhart’s arm designed to respond to signals from his brain, stimulate muscle fibres and cause movement in his paralysed hand. Photograph: Lee Powell/Washington Post

Comments